EEG-CLIP : Learning EEG representations from natural language descriptions

Recent advances in machine learning have led to deep neural networks being commonly applied to electroencephalogram (EEG) data for a variety of decoding tasks. EEG is a non-invasive method that records the electrical activity of the brain using electrodes placed on the scalp. While deep learning models can achieve state-of-the-art performance on specialized EEG tasks, most EEG analyses focus on training task-specific models for one type of classification or regression problem (Heilmeyer et al., 2018)

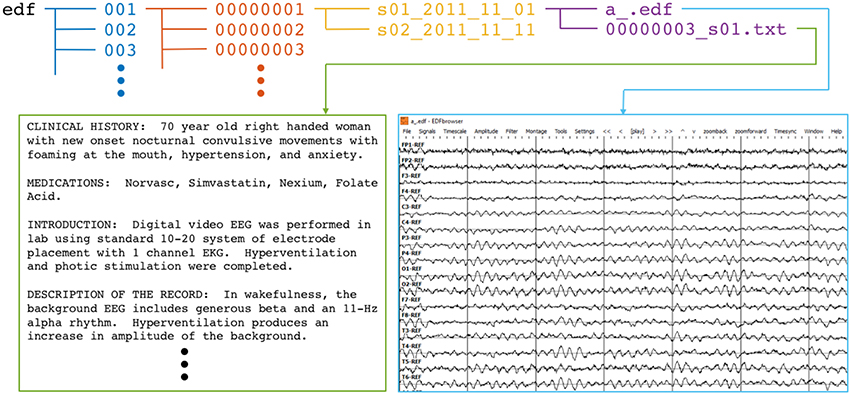

However, medical EEG recordings are often annotated with additional unstructured data in the form of free text reports written by neurologists and medical experts that can be exploited as a source of supervision.

|

|---|

| Overview of an annotated EEG record |

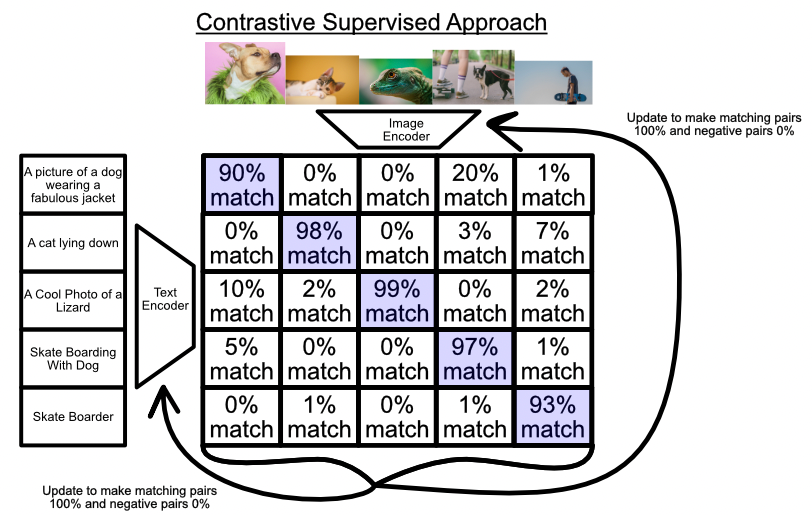

In the computer vision domain, Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training (Radford et al., 2021) leverages this text-image pairing to learn visual representations that effectively transfer across tasks. Inspired by CLIP, we propose EEG-CLIP - a contrastive learning approach to align EEG time series data with corresponding clinical text descriptions in a shared embedding space. This work explores two central questions: (i) how textual reports can be incorporated into an EEG training pipeline, and (ii) to what extent this multimodal approach contributes to more general EEG representation learning.

We demonstrate EEG-CLIP’s potential for versatile few-shot and zero-shot EEG decoding across multiple tasks and datasets. EEG-CLIP achieves nontrivial zero-shot classification results. Our few-shot results show gains over previous transfer learning techniques and task-specific models in low-data regimes. This presents a promising approach to enable easier analyses of diverse decoding questions through zero-shot decoding or training task-specific models from fewer training examples, potentially facilitating EEG analysis in medical research.

Methodology

Contrastive self-supervised learning has recently emerged as a powerful approach for learning general visual representations. Models like CLIP are trained to align image $x_i$ and corresponding text $y_i$ embeddings by minimizing a contrastive loss $\mathcal{L}$:

$\mathcal{L}=\sum_{i=1}^{N}-\log \frac{\exp(\text{sim}(x_i,y_i)/\tau)}{\sum_{j=1}^{N}\exp(\text{sim}(x_i,y_j)/\tau)}$

where sim(.) is a measure of similarity, such as cosine similarity, and $\tau$ is a temperature parameter that controls the softness of the distribution. This objective brings matching image-text pairs closer and separates mismatched pairs in the learned embedding space.

CLIP is trained on a vast dataset of 400 million image-text pairs from diverse Internet sources with unstructured annotations. Through this natural language supervision, CLIP develops versatile image representations that achieve strong zero-shot inference on downstream tasks by querying the aligned embedding space.

|

|---|

| Illustration of the constrastive learning process |

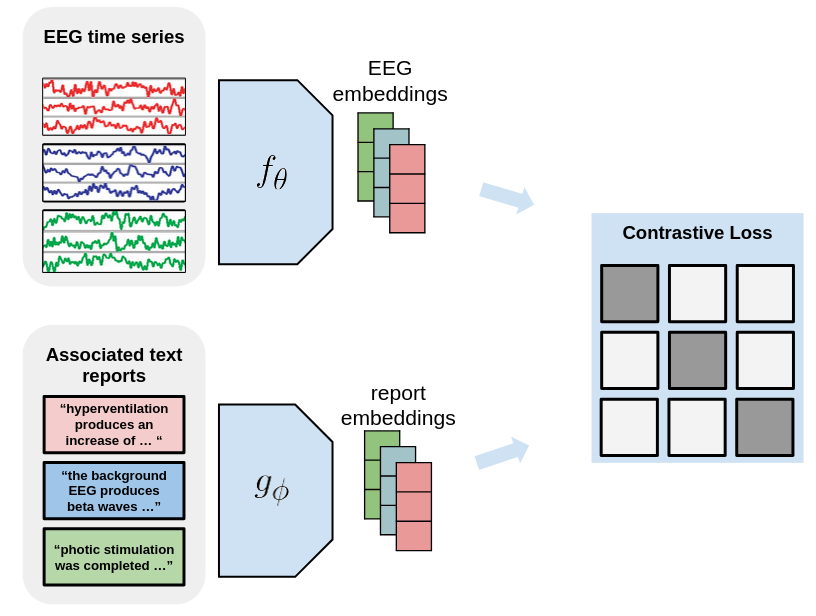

Inspired by the success of CLIP, we design EEG-CLIP as a contrastive learning framework for aligning EEG time series data with corresponding clinical text descriptions. EEG-CLIP consists of two encoder networks: an EEG encoder $f_{\theta}$ and a text encoder $g_{\phi}$. The EEG encoder $f_{\theta}$ maps the input EEG time series $x_i$ to a fixed-dimensional embedding vector $f_{\theta}(x_i)$, while the text encoder $g_{\phi}$ maps the corresponding clinical text description $y_i$ to an embedding vector $g_{\phi}(y_i)$.

The encoders are trained to minimize the contrastive loss $\mathcal{L}$, which encourages the embeddings of matching EEG-text pairs to be similar while pushing apart the embeddings of mismatched pairs. The similarity measure sim(.) used in EEG-CLIP is the cosine similarity between the normalized embeddings:

$\text{sim}(x_i, y_j) = \frac{f_{\theta}(x_i)^\top g_{\phi}(y_j)}{\lVert f_{\theta}(x_i)\rVert \lVert g_{\phi}(y_j)\rVert}$

Experimental Setup

In this section, we describe the dataset used for training and evaluating EEG-CLIP, as well as the experimental settings and evaluation metrics employed to assess its performance. We focus on the Temple University Hospital EEG Corpus Obeid and Picone, 2016, a large-scale dataset containing EEG recordings and their corresponding medical reports. The dataset’s size and diversity make it well-suited for training deep learning models to learn general EEG representations.

Dataset Description

The Temple University Hospital EEG Corpus Obeid and Picone, 2016 is a comprehensive dataset containing over 25,000 EEG recordings collected from more than 14,000 patients between 2002 and 2015. The dataset’s extensive size and variety of EEG recordings make it a valuable resource for training deep learning models to decode information such as pathology, age, and gender from EEG signals and generalize to unseen recordings.

For our experiments, we utilize the TUH Abnormal dataset (TUAB), a demographically balanced subset of the corpus with binary labels indicating the pathological or nonpathological diagnosis of each recording. The TUAB dataset is partitioned into a training set, consisting of 1,387 normal and 1,398 abnormal files, and an evaluation set, containing 150 normal and 130 abnormal files. The dataset encompasses a wide range of pathological conditions, ensuring a diverse representation of EEG abnormalities.

In addition to the binary pathology labels, each recording in the TUAB dataset is accompanied by several additional labels:

- “age”: An integer representing the patient’s age at the time of the recording.

- “gender”: A string indicating the patient’s gender, either “M” for male or “F” for female.

- “report”: A medical report written in natural language, providing a detailed description of the EEG findings and clinical interpretation.

The medical reports in the TUAB dataset are structured into 15 distinct sections, each focusing on a specific aspect of the EEG analysis. the following provides an overview of these sections and their respective contents.

| Record Section | Non-empty Entries | Average Word Count (Non-empty Entries) |

|---|---|---|

| IMPRESSION | 2971 | 16 |

| DESCRIPTION OF THE RECORD | 2964 | 70 |

| CLINICAL HISTORY | 2947 | 26 |

| MEDICATIONS | 2893 | 4 |

| INTRODUCTION | 2840 | 31 |

| CLINICAL CORRELATION | 2698 | 31 |

| HEART RATE | 1458 | 2 |

| FINDINGS | 887 | 16 |

| REASON FOR STUDY | 713 | 2 |

| TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES | 684 | 3 |

| EVENTS | 569 | 8 |

| CONDITION OF THE RECORDING | 116 | 30 |

| PAST MEDICAL HISTORY | 19 | 8 |

| TYPE OF STUDY | 16 | 3 |

| ACTIVATION PROCEDURES | 9 | 3 |

Evaluation metrics

Unlike models trained for a specific downstream task, EEG-CLIP aims to learn broadly useful representations that capture semantic relationships between EEG signals and text. As such, evaluation methods must aim to quantify the general quality and transferability of the learned representations.

Using the labels, meta-information, and medical reports provided in the TUAB dataset, we select four decoding tasks:

- “pathological”: Decode whether the recording was diagnosed as normal or pathological.

- “age”: Decode whether the age of the patient is smaller than or equal to 50, or greater than 50.

- “gender”: Decode the declared gender of the patient.

- “medication”: Decode whether the medical report contains at least one of the three most common anticonvulsant medications (“keppra”, “dilantin”, “depakote”).

We design multiple methods to evaluate the model, as described in the following subsections.

Classification

In this method, we use the representations learned by the EEG encoder of EEG-CLIP as features for the four classification tasks. The encoder representations are kept frozen, while a classifier is trained and evaluated on the “train” and “eval” sections of TUAB. This enables us to assess whether EEG-CLIP has learned to compress the discriminative information relevant for the classification tasks into its embeddings.

We compare this approach against two baseline models with the same architecture as the EEG encoder:

- The first baseline is a fully trainable model. This provides an upper bound on performance since the model can directly optimize for each task. Comparing EEG-CLIP to the trainable model reveals how much room there is for improvement over the fixed EEG-CLIP features.

- The second baseline is a model trained on an unrelated task, whose features are frozen while only the classification head is trainable. As these task-unrelated representations are not specialized for the actual decoding tasks, this serves as a lower bound on expected performance. The gap between the lower baseline and EEG-CLIP quantifies the benefits of our contrastive approach that can learn from all information contained in the medical reports.

By situating EEG-CLIP between these upper and lower bounds, we can better isolate the contributions of the learned representations themselves. Smaller gaps to the trainable model and larger gaps from the task-unrelated features indicate higher-quality multimodal representations.

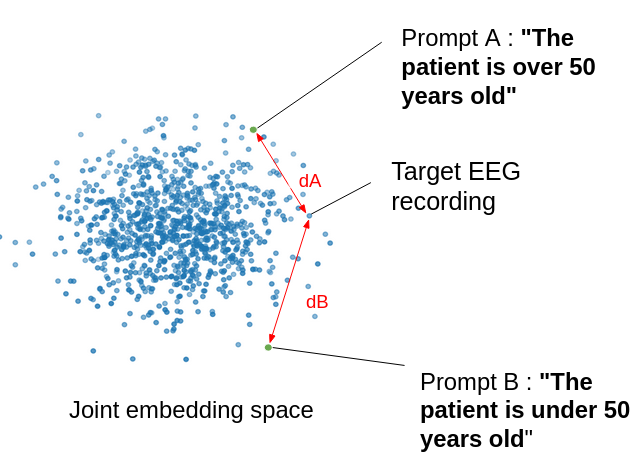

Zero-shot classification

We also perform zero-shot evaluation, using the embeddings of class-specific text prompts as class prototypes for the trained EEG-CLIP model. For a given classification task, we define a typical prompt sentence for each class and calculate the distance of an EEG recording to those sentences in the shared embedding space. This allows us to measure the classification performance of EEG-CLIP without any training on the classification task labels.

|

|---|

| Illustration of the zero-shot classification task |

| Task name | Prompt a | Prompt b |

|---|---|---|

| pathological | “This is a normal recording” | “This is an abnormal recording” |

| age | “The patient is over 50 years old” | “The patient is under 50 years old” |

| gender | “The patient is male” | “The patient is female” |

| medication | “No anti-epileptic drugs were prescribed to the patient” | “Anti-epileptic drugs were prescribed to the patient” |

Table 1: Prompts used for zero-shot classification

Classification in a low-data regime

To further evaluate the generalization capability of the learned representations, we assess few-shot performance by training the classifier on a small subset, held out from the training of EEG-CLIP. The limited labeled data setting reflects realistic clinical scenarios where large labeled datasets are difficult to acquire. New clinical applications often only have access to small patient datasets. As such, assessing few-shot transfer is important for demonstrating clinical utility and feasibility.

EEG data preprocessing

We preprocess the EEG data, taking inspiration from the preprocessing steps in Schirrmeister et al., 2018 The following steps are applied to the EEG recordings in the TUAB dataset:

- Select a subset of 21 electrodes present in all recordings.

- Exclude the first minute of the recordings and only use the first 2 minutes after that.

- Clip the amplitude values to the range of ±800 (\mu)V to reduce the effects of strong artifacts.

- Resample the data to 100 Hz to further speed up the computation.

- Divide by 30 to get closer to unit variance.

Architecture and training details

|

|---|

| Architecture of EEG-CLIP |

For the EEG encoder $f_{\theta}$, we use a convolutional neural network (CNN) called Deep4 -(Schirrmeister et al., 2018), whose architecture is optimized for the classification of EEG data. The Deep4 Network features four convolution-max-pooling blocks, using batch normalization and dropout, followed by a dense softmax classification layer. This enables the model to learn hierarchical spatial-temporal representations of the EEG signal. The output is flattened and passed to a fully-connected layer to derive a 128-dimensional embedding.

For the text encoder $g_{\phi}$, we leverage pretrained text encoders based on the BERT architecture (Devin et al). Such transformer-based models have shown state-of-the-art performance on a variety of natural language processing tasks. The advantage of these pretrained models is that they provide rich linguistic representations that can be effectively transferred to downstream tasks through fine-tuning.

The EEG and text embeddings are then fed into MLP projection heads, consisting of three fully-connected layers with ReLU activations. The final layer outputs a 64-dimensional projection of the embedding for contrastive learning. This architecture allows the model to learn alignments between EEG windows and corresponding medical report sentences in a shared embedding space. The contrastive loss enables the useful semantic features to be captured.

We train EEG-CLIP using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 5e-3 and weight decay of 5e-4. The model is trained for 20 epochs with a batch size of 64. We use the same training/testing split as in the TUAB dataset. Each recording is split into windows of length 1200, corresponding to a 12-second period, and with a stride of 519, which ensures all timesteps are predicted without any gap by our Deep4 model.

Results and Discussion

Classification

As shown in Table 2, on three of the four tasks, EEG-CLIP with a simple logistic regression classifier achieved strong performance, with balanced accuracy scores of 0.826 for pathological status, 0.687 for gender, and 0.713 for age. This indicates that the representations capture meaningful signal related to these key attributes.

| Task name | EEG-CLIP + LogReg | EEG-CLIP + MLP | Task-specific model | Irrelevant task + MLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pathological | 0.826 | 0.847 | 0.851 | 0.741 (age) |

| gender | 0.687 | 0.702 | 0.752 | 0.667 (pathological) |

| age | 0.713 | 0.747 | 0.786 | 0.685 (pathological) |

| medication | 0.633 | 0.615 | 0.685 | 0.573 (pathological) |

Table 2: Classification results (balanced accuracy on eval set)

With a 3-layer MLP classifier head, performance improved further on all tasks, reaching 0.847, 0.702, and 0.747 for pathological status, gender, and age, respectively. The MLP can better exploit the relationships in the embedding space.

As expected, the task-specific models achieve the top scores, as they are optimized end-to-end directly on the evaluation data distribution and labels. However, EEG-CLIP comes reasonably close, especially with the MLP head, demonstrating the generalizability of the representations.

Compared to irrelevant task pretraining, EEG-CLIP substantially outperforms models pretrained on inconsistent targets like age or pathology. This confirms the importance of learning from the information contained in the medical reports.

Zero-shot classification

| Task name | Balanced accuracy on eval set |

|---|---|

| pathological | 0.755 |

| age | 0.642 |

| gender | 0.567 |

| medication | 0.532 |

Table 3: Zero-shot classification results

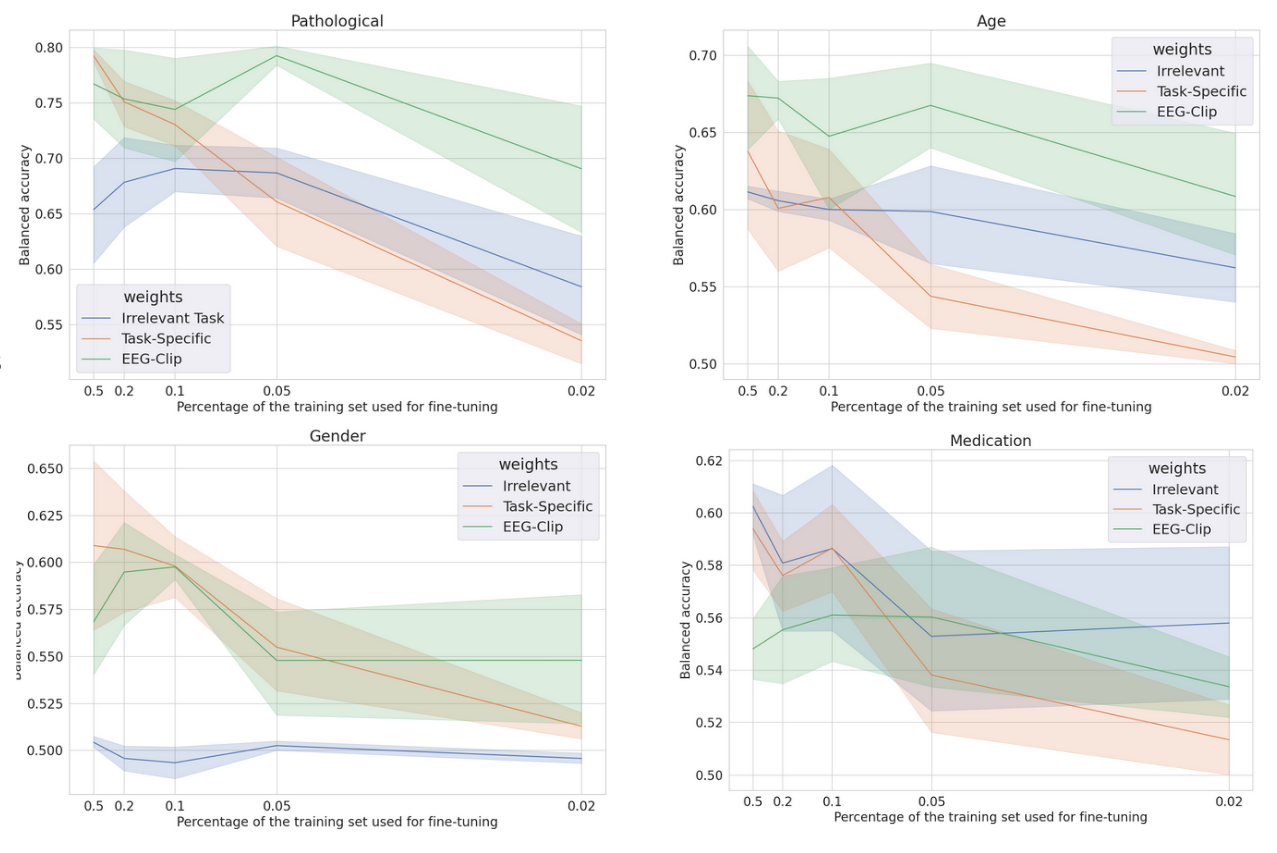

Classification in a low-data regime

| Task name | EEG-CLIP + MLP | Task-specific model | Irrelevant task + MLP |

|---|---|---|---|

| pathological | 0.710 | 0.781 | 0.531 (age) |

| gender | 0.550 | 0.648 | 0.512 (pathological) |

| age | 0.712 | 0.621 | 0.631 (pathological) |

| medication | 0.551 | 0.575 | 0.598 (pathological) |

Table 4: Classification results in low-data regime (balanced accuracy on eval set)

On the pathological task, EEG-CLIP achieves 0.710 balanced accuracy on the held-out set. This approaches the 0.781 performance of a model trained from scratch with the same limited data. For age classification, EEG-CLIP even outperforms the specialized model. The medication task proves most challenging in the few-shot setting. However, all models struggle to exceed 0.6 accuracy, suggesting intrinsic difficulty of the binary prediction from small samples.

Critically, EEG-CLIP substantially outperforms models pretrained on irrelevant tasks across all but one experiment. This demonstrates the concrete value of pretraining on aligned data, even when fine-tuning data is scarce.

|

|---|

| * Few-shot accuracy for each task, for different training set sizes as fractions of the original training set size * |

Taken together, these quantitative results provide strong evidence for the quality and transferability of the multi-modal representations learned by EEG-CLIP. Performance across the range of evaluation paradigms demonstrates that it successfully encodes general semantic relationships between EEG and text.

Future Work and Conclusion

The EEG-CLIP framework presents a promising approach for learning versatile representations from EEG data by leveraging the information contained in medical reports. However, there are several potential avenues for future research to further improve and extend this framework.

One direction is to expand the training data by including more EEG recordings and their corresponding medical reports. As the EEG-CLIP framework relies on EEG-text pairs and does not require additional labeling, increasing the size and diversity of the training dataset could lead to more robust and generalizable representations. This is particularly advantageous since obtaining EEG-text pairs is relatively inexpensive compared to manually labeling EEG data for specific tasks.

Another exciting future direction is to explore the development of general-purpose pretrained EEG encoders using the EEG-CLIP framework. Similar to how pretrained language models like BERT have revolutionized natural language processing, pretrained EEG encoders could serve as a foundation for various EEG-related tasks. For example, pretrained encoders could be fine-tuned for specific applications such as motor task classification, emotion recognition, or sleep stage scoring, potentially reducing the need for large labeled datasets in each individual domain.

The significance of the EEG-CLIP framework lies in its ability to enable easier analyses of diverse decoding questions through zero-shot decoding or training task-specific models from fewer examples. By learning to align EEG signals with their textual descriptions, EEG-CLIP can perform classification tasks without explicit training, as demonstrated by the zero-shot classification results. Furthermore, the model’s strong performance in low-data regimes highlights its potential for adapting to new tasks with limited labeled data, which is particularly valuable in medical research where obtaining large annotated datasets can be challenging.

In conclusion, the EEG-CLIP framework introduces a novel approach for learning versatile representations from EEG data by leveraging the information contained in medical reports through contrastive learning. The main contributions of this work include the development of a multimodal contrastive method that aligns EEG signals with their textual descriptions, the demonstration of its ability to outperform task-specific models in low-data regimes, and the showcase of zero-shot classification capabilities. The potential impact of EEG-CLIP on EEG analysis in medical research is significant, as it could facilitate the exploration of diverse decoding questions and enable more efficient development of EEG-based applications. With future extensions such as expanding the training data and building general-purpose pretrained EEG encoders, the EEG-CLIP framework has the potential to revolutionize the field of EEG analysis and contribute to advancements in neurological disorder diagnosis, brain-computer interfaces, and beyond