Q-Learning : Learning (by yourself) the rules of the game

I’ve always wondered how artifical intelligences could operate in video games. How could the ennemies in a game could possibly know how and when to attack, flee, or trick the player depending on the context ?

It turns out that is fact, in the majority of games, the AIs behavior is coded by a simple list of conditions: video game developpers usually determine by advance a list of states the game can be in, and, for each of these states, decide of a list of actions for the AI to execute. In a relatively simple game like Pacman, it could turn out like this :

A pacman game : two states (invicible mode, non invincible mode) and two possible corresponding actions (attack PacMan, flee from PacMan)

A pacman game : two states (invicible mode, non invincible mode) and two possible corresponding actions (attack PacMan, flee from PacMan)

This way of programming an AI, called Finite State Machine, is a simple method allowing to create agents that can adapt to the game environment. Lets try for example to write the list of states and actions for a tic-tac-toe game :

| Etat | Action |

|---|---|

| The central spot is free | Play in the central spot |

| A lateral spot is free | Play in the lateral spot |

| The opponent has two aligned marks | Block him |

| I have two aligned marks | Complete the line |

At each turn, the program will observe the game state and will do the corresponding action.

This method is good for creating agents adapting to the opponents actions. However, it requires to think in advance about this list of states and actions. This implies for the developper to already have a good, if not perfect, understanding of the rules of the game, and its winning strategies. Indeed, if the program finds itself, by misfortune, in a state that was not planned in advance, it will simply not know what action to take and will be blocked.

An interesting way to proceed would be to find a way to make the program builds its own strategy, as the games progress. A bit like humans do : when playing a new game, we don’t need to know in advance the details of the winning strategies. We simply acknowledge the rules, and, over time, we learn which actions are the most likely to lead us to victory.

The basics of operation

We will try to create a program that learns to play tic-tac-toe by itself. Lets first try to describe how could this program look like.

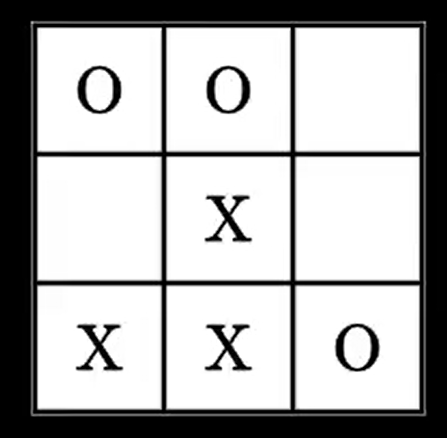

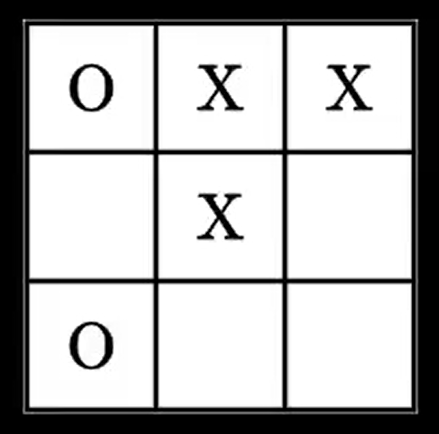

During a game, at each step, the games board will be made of a certain arrangement of crosses and circles, for example this one :

or this one :

In total, the player can be faced with 5478 different dispositions, or states.

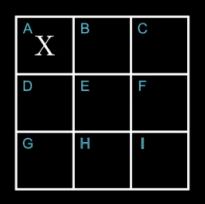

At each turn, the program will find itself in one of these states, and will have to perform an action, i.e. play somewhere. The game board being made of 9 squares, there are at most 9 possible actions, which can be labeled from A to I:

We will give our program a goal to reach: Maximize a number of points during its games. For each game, we give it 1 point when it wins, and -1 point when it loses.

Let’s illustrate this mechanism with an example, in a random state. Here, the program can play in B, F and H.

If the program plays B or F, it will win the game: +1 point for it. If he plays in H, it is very likely that the opponent will play in F at the next move: -1 point.

If the program plays B or F, it will win the game: +1 point for it. If he plays in H, it is very likely that the opponent will play in F at the next move: -1 point.

Let’s imagine for a moment that we had previously succeeded in evaluating the points earned by each of the 9 actions, in the 5478 states.

The set of points brought by the 9 possible actions, for each of the 5478 states.

The set of points brought by the 9 possible actions, for each of the 5478 states.

If we can evaluate perfectly how many points each action brings in each state, we can simply ask the program to look, each time it encounters a state, for the action that will bring in the maximum number of points, and perform this action:

Action(t) = argmax( Table[State(t)] ) The program performs the action that gives it the most probable points, according to the values in the table.

The program performs the action that gives it the most probable points, according to the values in the table.

Learn by making mistakes

But then, how to evaluate the points that each action yields, for each state? You can simply let the program play randomly, and observe by itself the points it gets for each action it makes. As it plays, it will gain experience and adapt its behavior.

Let us note R the reward obtained after having carried out an action in a given state. The new value associated with the current state and action will be :

Table[ State(t), Action(t)] = R When we receive a reward after an action, we update the corresponding value of the table.

When we receive a reward after an action, we update the corresponding value of the table.

However, we notice a problem with our operation: Not all actions in the game are immediately rewarded. Indeed, in tic-tac-toe, a game lasts between 5 and 9 moves, and only the last action earns or loses a point.

In fact, before each action, the program takes into account the reward it will have immediately, but not those of the following rounds: it does not have a “long-term vision”. This is however a fundamental ability when you want to build a strategy over several rounds.

No strategy without long-term vision

To fix this, we’ll make the program take into account the likely rewards it could have in the following rounds:

When it does an action, the program will observe the reward R it gets immediately, but also evaluate the future reward R_next, evaluated as the maximum of the possible rewards in the new state.

R_next = max( Table[State(t + 1)] )

Table[ State(t), Action(t)] = R + R_NextIn this way, as the game progresses, the table will consist not only of the immediate rewards of each action, but also of the more distant probable rewards.

Putting it into practice

We can now play our program and see how it does. We will have to find an opponent for it: we can find an AI in any tic-tac-toe game available on the Internet. Let’s pick one and play it against our program.

At the beginning, our program is systematically beaten. But after about 1000 games, it starts to win, and ends up not letting its opponent win any game.

He is well trained, and knew how to find a strategy to beat his opponent every time. Let’s try to see if he can beat a human ?

Putting it into practice (for real)

While playing ourselves against the program, surprise : it is really lame. It doesn’t even try to block us, nor to complete a line. It gets beaten every time…

So why doesn’t it show any signs of strategy when it did so well against the AI found on the Internet?

In reality, we put in front of our program an AI with a unique strategy, coded in Finite State Machine: it will always adopt the same behavior in a given situation. After many games, the program is super-trained against the AI’s strategy, but is not trained at all against another opponent with another strategy.

So, how can we vary the strategies encountered by our program, so that it becomes stronger against a possible new opponent? Several solutions are available to us:

- We could add, from time to time, random moves during the games. Our program could then face new situations that are not part of the opponent’s strategy;

- We could also find several AIs with different strategies, and make it fight against each of them in turn;

- A third solution, simpler, would be simply to create several programs, with the same functioning as the first one, and to make them play against each other.

The third solution is simpler, and in a sense, more interesting : by making naive agents play against each other, without them having any knowledge about strategies beforehand, we could make new and efficient strategies naturally emerge.

We choose to make play 10 agents against each other. And this time indeed, after 1000 plays, the best agent is able to have a strategy against a human play : He has encountered a sufficient number of different strategies during his training.